In an earlier blog, we explored some best practices for documenting Agile Product Requirements. Product requirements are the common language between business and engineering that play a vital role because they are the first step in the product development process – where value creation is highest. In Agile projects, project requirements documentation should evolve and stakeholders collaborate to keep documentation as light as possible, while providing the necessary information to design and complete a Sprint. Requirements definition leads to the next step in the software development life-cycle, the technical design. This is a critical phase of the SDLC that often gets overlooked because it is not directly linked to a visible part of the product.

Why Technical Design Matters

Technical Design is closely tied to the underlying technical architecture of the product you are building, and is intended to provide the developer with the right level of detail to be able to build the feature. It serves as the “architectural blueprint” that developers and testers can follow in developing the features. It is not to be confused with Functional Design, whose purpose it is to specify the design elements associated with the functional description – such as process flows, UI screens and business rules.

The benefits of a well-managed technical design effort can go deep in your organization. Well documented Technical Designs can help improve team communication across various functions, improve knowledge sharing and on boarding new team members. Ignoring or overlooking design documentation can lead to poor visibility and tribal knowledge that can impede ongoing development efforts and particularly on boarding and training new team members. Unfortunately a lot of Agile teams today do not have the time or resources to document the design well. As a result, the level of design documentation is minimal to practically non-existent. Having to go through source code to understand technical design is not where you want to end up. This is a real challenge as it hinders progress on multiple fronts. We present a general approach and some best practices for documenting Technical Design in this blog.

Design Methodologies

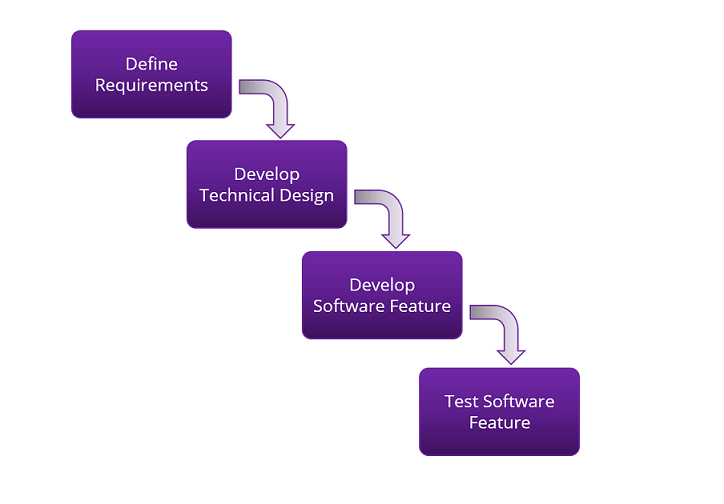

Let’s start by considering a methodology for design, which is the framework, organizational model and activities that will get us from business requirements to the start of development. Waterfall and Agile are perhaps the two well-known methodologies that most companies have worked with at some point. The waterfall method is a linear, sequential (non-iterative) design approach for software development in which progress flows in one direction downwards (like a waterfall) through the phases of conception, initiation, analysis, design, development, testing and deployment. The waterfall methodology maintains that a project phase should move to a next phase only when it’s preceding phase is reviewed and verified.

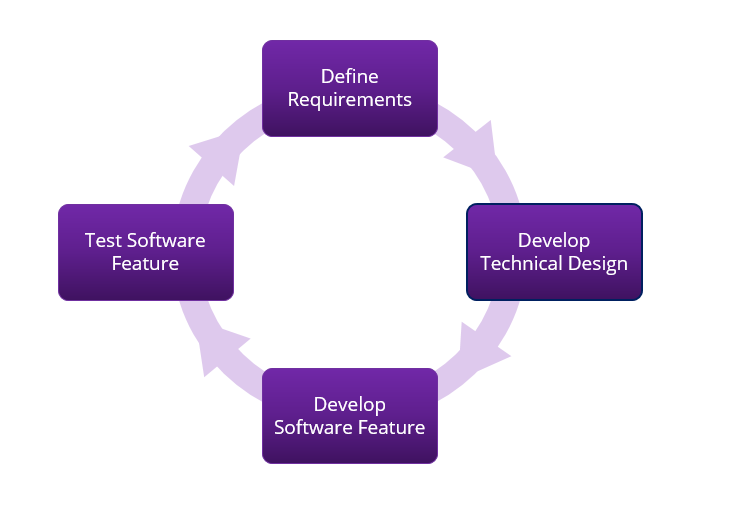

The Agile Methodology refers to a group of software development methodologies based on iterative software development, where requirements and solutions evolve through collaboration. Agile methods generally promote a disciplined project management process that encourages frequent review and adaptation, teamwork, accountability and a business approach that aligns software development with customer needs and company goals. Agile is primarily about the “how of a project” with planning done in portions (Sprints) rather than as a whole. The particular scope of work is usually variable, while time and quality are fixed.

Recognizing the fundamental difference between each methodology, some similarities do exist. Both methodologies use input from outside the team that is doing the work. Project team members conduct user research, gather business needs and discuss technology possibilities—the fruits of this effort are the Product Requirements Document and the Design Document.

Tools for Design

For whatever design methodology you choose, the process is best enabled with a concise set of tools. Here is what we prescribe.

User Story. A user story is a basic tool used in Agile development to capture a description of a software feature from an end-user perspective. Sometime called a scenario, the user story describes the type of user, what they want and why. It helps to create a simplified description of a requirement. It is usually written out as a couple of sentences, and written in the language of the users, so any user should be able to read a user story and readily understand what it means. Note that a Use Case is somewhat similar to a User Story but it describes one specific interaction between the user and the software. A user story is a good organizing concept for developing and documenting the Technical Design. Each user story needs to have a technical design associated with it.

UI design is accomplished, or aided, with a wireframe, which is a schematic visual representation of a user interface. The wireframe is used to define the layout of items on a screen and communicates what the items on that page should be based on user need. The wireframe depicts the page layout including interface elements and navigational systems, and how they function together. The wireframe usually lacks typographic style, color, or graphics, since the main focus lies in functionality, behavior, and priority of content. The UI design is a part of the Functional Design, and not the Technical Design.

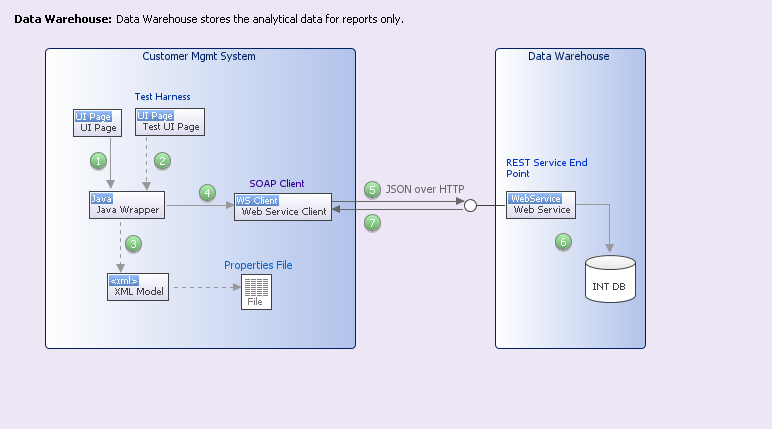

Design Patterns. Simply defined, a design pattern is a general reusable solution to a commonly occurring problem within a given context of the project. It is not a complete design that can be transformed directly into code. It is a description or template for how to solve a problem that can be used in many different situations. Design patterns are often formalized best practices that can be used to solve common problems when designing an application, product or system. They can speed up the development process by providing tested, proven development paradigms. They also allow you to leverage scale economies through standardization. We recommend keeping design patterns at a component level, that is, at a higher level of abstraction than class-level design tools such as UML diagrams. Component level design patterns are easy to understand and manage. An example of this is shown in the figure below.

Integration Points and Interfaces. We live in an API driven economy. Integration points and interfaces are everywhere and require a solid understanding, and clear documentation, throughout the design process. Both terms describe how a software solution will share data with other software. A software interface is a bridge that allows two programs to share information with each other, even though they may have been developed by different sources or use different programming languages. Data is typically maintained in multiple locations. Software integration involves products that work together seamlessly as one solution.

Interfaces and integration points should be designed with a systematic process involving service endpoint selection, service authentication, workflow development, object and data field mapping, data transformation mapping, and events and synchronization mapping. Design diagrams are very useful for developing and displaying these design elements. A library of standardized and repeatable architecture patterns for integration points increases efficiency and encourages standardization.

Design Documents

The goal of the Design Document is to clearly articulate the design components involved and the logical sequence of program flow between them. We recommend keeping design diagrams at a component level, that is, at a higher level of abstraction than class-level design tools such as UML diagrams. For example, these could include a database, a web service end-point, a message queue, a UI page or a helper utility. It is really hard to keep up with all the churn at the class-level design. User stories, user interface design features, and interface/integration points are best documented in a centralized, dynamic and visually managed ‘System of Record’ for design, rather than disparate Word, Excel documents or Visio documents. These tools allow you to manage your library of reusable Design Patterns – key building blocks for managing the complexity arising from a vast landscape of enterprise IT. Automation is the central theme in these tools, empowering team members to automate routine, tedious documentation tasks that do not add value. Users can automatically generate a detailed Design Document for UI features and for integration points. This helps save significant amount of time for architects and developers, and enables improved team communication and collaboration, up to date documentation and lowers execution risk.

Closing Thoughts

Agile design acknowledges that a project is going to be flexible and evolving, and to put processes in place that allow it to be that way. Either Agile Design or Waterfall (or some hybrid) provide the process to rapidly synthesize product requirements into a usable design to complete a project phase (Waterfall) or sprint (Agile). The use of standardized design tools improves efficiency and reduces ambiguity. Finally, as with Product Requirements Documents, best practices for fluid design documents comprise synchronized efforts that encourage sharing and collaboration. The benefits of a well-managed design effort go well beyond just the developers – your entire team can benefit from improved visibility and collaboration. Ignoring or overlooking Design Documentation can lead to poor visibility and lack of shared knowledge that can impede ongoing development efforts and particularly onboarding and training new team members.

What are your organization’s experiences around managing Technical Design in an Agile environment? What challenges have you faced and how did you overcome them? We would love to hear from you in the comments section below.